|

|

Post by User Unavailable on Nov 1, 2013 21:09:18 GMT

We've discussed several times about the smoke of cannon fire obscuring the battlefield. Here is a pic from a recent Civil War reenactment I attended, where the weather conditions were just right for the smoke to linger and cling to the ground. Almost no wind, cool and humid air. This is smoke from 3 Union Cannon and 4 Confederate cannons. This is smoke hanging around after just the first of several volleys of cannon fire.  When I get it uploaded, I'll link the video of the battle and you can see how thick the smoke got, so that the battle was almost completely obscured at times. |

|

|

|

Post by Cybermortis on Nov 1, 2013 21:38:40 GMT

Very nice.

I knew about the thickness of the smoke, but only from written records and some paintings - usually paintings done by artists who were present at a battle. Nice to get a 'real' world image to see what it was really like.

Makes you realise why the term 'fog of war' came into use.

|

|

|

|

Post by the light works on Nov 1, 2013 23:54:20 GMT

really drives home the anecdote about the cannons and muskets being primarily to lay down a smokescreen for the bayonet charge.

(note: anecdote, not myth)

|

|

|

|

Post by silverdragon on Nov 2, 2013 7:45:24 GMT

Is this the reason why "Spotters" were first included?...

Someone to actually stand clear of the smoke and spot where shots landed..........

|

|

|

|

Post by the light works on Nov 2, 2013 12:10:20 GMT

Is this the reason why "Spotters" were first included?... Someone to actually stand clear of the smoke and spot where shots landed.......... my wild guess would be probably not - as they would have little to no way to communicate with the gunners. I would guess the spotter came about when they first realized with a good cannon, you could shoot things that were hiding behind hills; at which point you could see the spotter, but not the target. |

|

|

|

Post by User Unavailable on Nov 2, 2013 16:43:26 GMT

There was "some" artillery spotting that went on during the Civil War, though it wasn't a common thing as the limited range of most artillery relegated it to role of Direct Fire weapons, meaning they typically shot at what they had a line of sight to.

There were only two ways of "quick" communications from a spotter at a distance. Telegraph or semaphore.

The Union employed both from tethered balloons(confederates used at least semaphore) for spotting troop movements and in some cases directing artillery fire. Though both sides had pretty much abandoned balloons in 1863.

Forward Observers really came into modern usage during WWI, when much longer range artillery was employed on a massive scale in an Indirect Fire role.

Methods and procedures for calling for and adjusting fire were developed and FO's would creep out to various positions stringing out a spool of communications wire behind them to make use of a field telephone to relay fire commands. Of course balloons and airplanes were also used.

|

|

|

|

Post by the light works on Nov 2, 2013 16:45:39 GMT

hadn't thought of a telegraph in a tethered balloon. guess it illustrates that old adage about necessity and invention.

|

|

|

|

Post by Cybermortis on Nov 2, 2013 17:21:35 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by silverdragon on Nov 3, 2013 8:06:26 GMT

Runners?...

No, Seriously, the spotter sends a runner to the guns and back, maybe even a team of them....

I can see the sense in that, and I sort of half-remember-something-I-once-heard that this is how we invented, or rather re-invented the messenger thing, which got as far as the motorbike courier....

|

|

|

|

Post by Cybermortis on Nov 3, 2013 13:16:57 GMT

Runners?... No, Seriously, the spotter sends a runner to the guns and back, maybe even a team of them.... I can see the sense in that, and I sort of half-remember-something-I-once-heard that this is how we invented, or rather re-invented the messenger thing, which got as far as the motorbike courier.... 'Runners' were used to send orders from the commander to the individual units, and to keep the commander informed as to the state of a unit. Of course 'runner' mean a man on horseback. As far as artillery goes this wouldn't have worked very well for correcting fire. If they were firing at a stationary target the gun crews could spot for themselves, if they were firing at a moving target - that is an advancing infantry unit - then any information they could get from a runner would be badly out of date by the time it reached them. There were very detailed tables detailing the range for each type of gun using various types of shot and powder charge and of course elevation. So gunners only needed to know how far they were from a target to be able to set the guns correctly. For fixed targets, such as fortifications, this was simplicity itself. For moving targets - meaning infantry - the rate of closure would be fairly constant which would allow gunners to make reasonable guesses as to when they needed to adjust their fire. Things were a little more complex at sea. On one hand it was usually fairly easy to see exactly where your opponent was, both because you were shooting at a large target and because you could see their masts above the smoke*. On the other hand estimating range and speed was difficult to say the least, so even if you discounted the additional problems the movement of the deck caused in aiming effective gunnery range at sea tended to be lower than on land** Mortars were a different matter, as unlike cannons they were (in theory) indirect weapons. However from what I can tell it seems that mortars had a lower range than cannon, so not only tended to be used in a directly line of sight to their target - allowing the gunners to judge the fall of shot for themselves - but also behind a line of cannon. Their inaccuracy made them only really useful against large immobile targets, or as area effect weapons, rather than as the more precise weapons that exist today. Of course you could say that about most of the artillery used in the blackpowder age. (*The topmasts at least. Several of the paintings we have of naval battles, painted by artists who were there for that battle or who were naval officers themselves, show that the smoke produced by a broadside could obscure everything from the bowspit to the poopdeck, and between the waterline and mainyard.) (**Of course this is for guns of the same calibre. Naval guns tended to be a lot larger than their army equivalent, so had a larger 'natural' range. In practice it appears that the maximum practical range for field and navy guns was not that dissimilar, most likely due to the difficulty in aiming guns and lack of effective sights for them.) |

|

|

|

Post by User Unavailable on Nov 4, 2013 5:24:35 GMT

I will have to get my son to edit the video for me, when he has time. It is too big to upload to photobucket.

|

|

|

|

Post by tacitus on Dec 5, 2014 1:48:40 GMT

If I can revive a slumbering thread for a moment . . .

Spotters are really only useful if your weapon and crew have a few necessary capabilities. Your piece must have the capability to return almost exactly back to battery after firing. For field pieces (we're not talking mortars), the pieces normally recoiled out of battery when fired, and while they could be rolled back forward, there was virtually no ability to return the barrel to the exact original alignment. As a result, any correction the spotter made (especially in deflection) would be meaningless as you would not be correcting from the same alignment. For example, the spotter may call for an adjustment to the right, but if, after you pushed you piece back into position you unknowingly had the barrel pointing a few degrees right of where it originally was, any adjustment you made to the right would probably over-correct. Or, if you ended up a bit to the left of your original alignment, it would probably nullify the spotter's correction.

The advent of soft recoil mechanisms (a la the French 75's hydro-pneumatic short recoil system), improved gunner optical sights and the use of fixed aiming stakes finally made it possible to ensure the tube was back to its original alignment, and provided a precise method of measuring changes of elevation and deflection to adjust for the spotter's call. [Various versions of gunner's quadrant sights had been around for quite some time to handle elevation, but it wasn't until the WWI era that optical gunner's sights became really efficient.] In turn, this required the development of new gunnery procedures in spotting. A spotter's correction of 'right 400 yards' means nothing to a gunner who can't see 50 yards in front of him. You have to take the correction, account for the range, and convert the adjustment to an angular correction that can be used by the gunner on his sights. And that assumes the gunner and spotter are looking at the target along the same line, which in reality they almost never do. Which in turn eventuallly led to the development of the fire direction center (as mentioned earlier).

It took the combination of many technologies and procedures before the use of spotters for field artillery became a practical and reliable system. Unfortunately, that meant several centuries of firing half-blind at indistinct blobs or waiting until very close range.

Mortars didn't have that problem as their beds generally didn't displace significantly as a result of a firing and corrections could be more easily applied. Hence they could be adjusted onto stationary targets fairly easily by a spotter. Later generations of sea coast cannon had sophisticated carriages that both returned the cannon precisely back to battery and enabled precise deflection adjustments, too. So these classes of weapons could - and did- benefit from spotters at an earlier point.

|

|

|

|

Post by Cybermortis on Dec 5, 2014 12:17:59 GMT

Thinking about it one of the problems with early guns and spotters would have been communicating with each other - after the first shot from a battery chances are everyone would be deaf. This would probably explain why experienced gun crews were in such demand, it wasn't that they could automatically load and fire faster rather they were probably so used to working together they could communicate without having to speak.

The first appearence of sights for cannon and elevation I know of came in the latter part of the 1700's. I *think* the carronade had (or some had) markings for elevation (they also had carriages that absorbed the recoil) and certainly they were elevated through the use of screws rather than the wooden blocks used for the great guns.

The first ship I can think of that I know had its great guns fitted with sights was HMS Shannon in 1813. She was unusual in this regards as sights were not issued to Royal Navy ships at this period, and in fact the equipment had been installed by Captain Brooke at his own expense. However the implication is that such equipment and technology was available and that Brooke was probably not the only Captain (or HMS Shannon the only ship) to have such equipment or who would have liked it. Brooke was independently wealthy, and hence able to afford to buy the equipment. Most Captains however were neither 'gunnery' Captains or wealthy enough to afford such equipment - many had enough trouble maintaining the expected standards at the Captains table, and often had to borrow money to get dinner services suitable for a representative of the King.

Post 1815 such sights fell out of favour with the navy. An educated guess would be that this was because they were only really useful for long-range fire, which seems to have been unusual in the age of sail or at least not something the Royal Navy did all that often with the main guns. Closer in smoke would have obscured vision, and the noise deafened the gun crews to the point that they would not have been all that useful. The sights didn't play any real part in the Shannon's battle against the Chesapeake. It wouldn't have helped that the elevation of a ships guns would be constantly changing as the ship rolled.

|

|

|

|

Post by the light works on Dec 5, 2014 16:40:00 GMT

our TV show Top Shot featured an 1877 (replica) Hotchkiss Mountain Gun - which had an optical sight which the gunner would mount to aim the gun and then remove for firing.

|

|

|

|

Post by tacitus on Dec 6, 2014 3:32:38 GMT

The first ship I can think of that I know had its great guns fitted with sights was HMS Shannon in 1813. She was unusual in this regards as sights were not issued to Royal Navy ships at this period, and in fact the equipment had been installed by Captain Brooke at his own expense. However the implication is that such equipment and technology was available and that Brooke was probably not the only Captain (or HMS Shannon the only ship) to have such equipment or who would have liked it. Brooke was independently wealthy, and hence able to afford to buy the equipment. Most Captains however were neither 'gunnery' Captains or wealthy enough to afford such equipment - many had enough trouble maintaining the expected standards at the Captains table, and often had to borrow money to get dinner services suitable for a representative of the King. Broke was a gunnery wizard by anyone's measure. Not only did he weld dispart sights on all guns and carronades but also issued wooden quadrant sights (gunners levels) for setting degrees of elevation. To mass fires he had a compass carved at every gunport, with the grooves filled with white putty; using the marks on the compass permitted all gunners to individually set deflections so as to aim at the same common point for given rehearsed ranges, even if the target were obscured from the gun captains' view. Peace nurtures professional complacency. Were it not for the fact that Britian had effectively gained naval supremacy by 1813, and the advent of a long peace thereafter, perhaps his innovations may have made a greater impact. As it was, most captains of most navies were of Nelson's view: “As to the plan for pointing a gun, truer than we do at present, if the person comes, I shall, of course, look at it, or be happy, if necessary, to use it; but I hope we shall be able, as usual, to get so close to our enemies that our shot cannot miss the object.” |

|

|

|

Post by tacitus on Dec 6, 2014 4:41:23 GMT

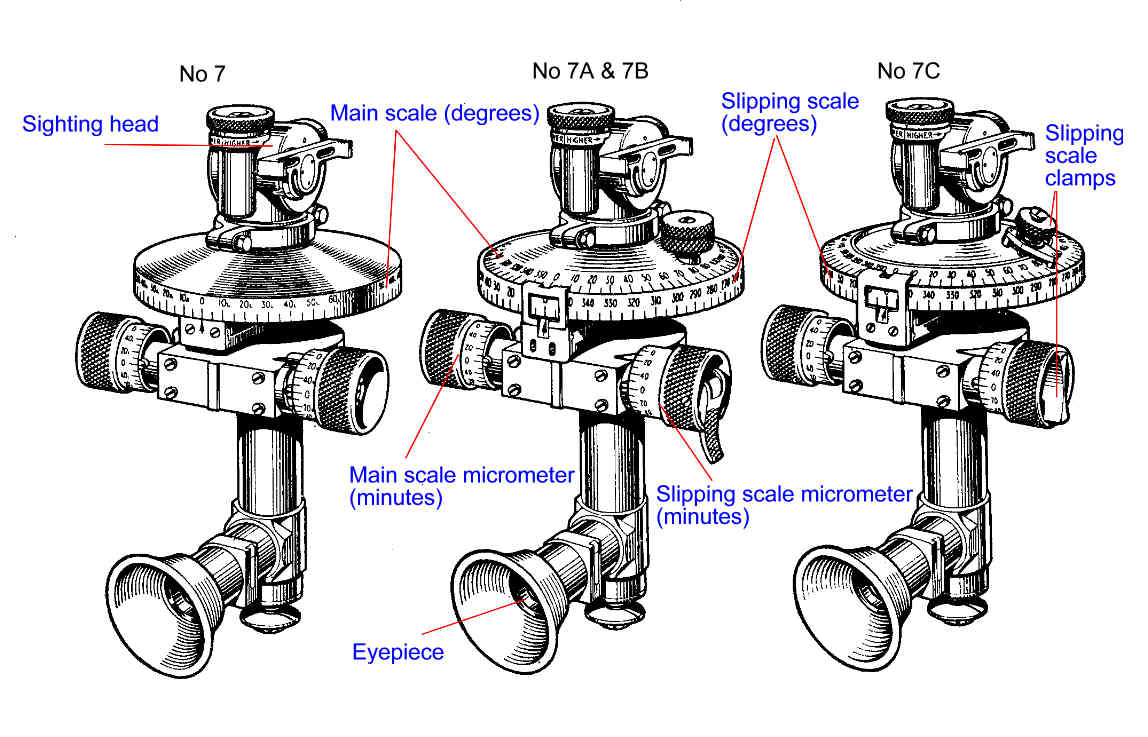

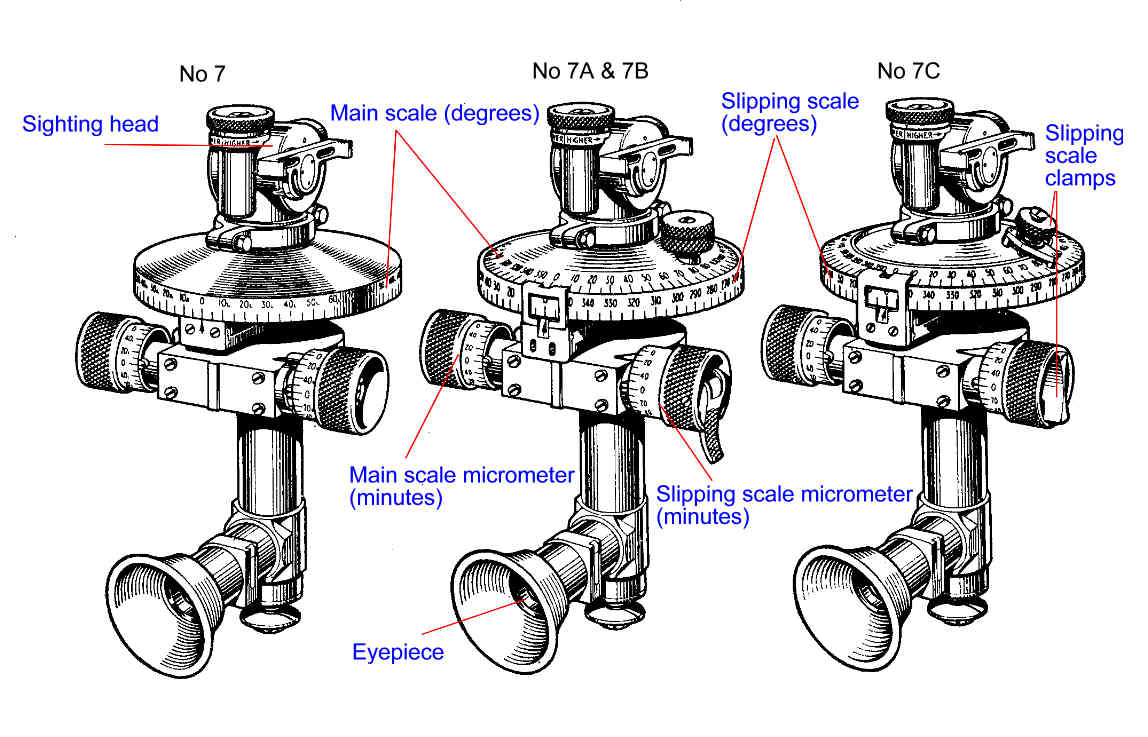

our TV show Top Shot featured an 1877 (replica) Hotchkiss Mountain Gun - which had an optical sight which the gunner would mount to aim the gun and then remove for firing. Yeah, I should have been more specific. I was refering to the development of goniometric sights. 'Optical' was a pooly chosen adjective. The British Dial sight was a development of goniometric sights as was the US panoramic sights. The No. 7 Dial sight, for example, was fielded to British artillery in 1910 as the science of indirect fire was coming together.  The Hotchkiss sight was only for direct lay, as far as I know. Modern(ish) goniometric sights permitted precise angular measurements from fixed reference points (i.e., aiming stakes) for accurate setting of deflection in indirect firing. They are also used in conjunction with Directors (British) / Aiming Circles (US) to align all the tubes in a battery exactly paralell. For anyone who can't sleep, some gunnery info (Warning - lots of pop-ups!): nigelef.tripod.com/directory.htm |

|

|

|

Post by the light works on Dec 6, 2014 4:49:56 GMT

our TV show Top Shot featured an 1877 (replica) Hotchkiss Mountain Gun - which had an optical sight which the gunner would mount to aim the gun and then remove for firing. Yeah, I should have been more specific. I was refering to the development of goniometric sights. 'Optical' was a pooly chosen adjective. The British Dial sight was a development of goniometric sights as was the US panoramic sights. The No. 7 Dial sight, for example, was fielded to British artillery in 1910 as the science of indirect fire was coming together.  The Hotchkiss sight was only for direct lay, as far as I know. Modern(ish) goniometric sights permitted precise angular measurements from fixed reference points (i.e., aiming stakes) for accurate setting of deflection in indirect firing. They are also used in conjunction with Directors (British) / Aiming Circles (US) to align all the tubes in a battery exactly paralell. For anyone who can't sleep, some gunnery info (Warning - lots of pop-ups!): nigelef.tripod.com/directory.htmyes - and the video said the Hotchkiss was a direct fire gun. interestingly, being a breechloader, the competitors were taught to start by boresighting it at the target and then use the optics to fine tune their aim. |

|

|

|

Post by Cybermortis on Dec 6, 2014 12:09:24 GMT

The first ship I can think of that I know had its great guns fitted with sights was HMS Shannon in 1813. She was unusual in this regards as sights were not issued to Royal Navy ships at this period, and in fact the equipment had been installed by Captain Brooke at his own expense. However the implication is that such equipment and technology was available and that Brooke was probably not the only Captain (or HMS Shannon the only ship) to have such equipment or who would have liked it. Brooke was independently wealthy, and hence able to afford to buy the equipment. Most Captains however were neither 'gunnery' Captains or wealthy enough to afford such equipment - many had enough trouble maintaining the expected standards at the Captains table, and often had to borrow money to get dinner services suitable for a representative of the King. Broke was a gunnery wizard by anyone's measure. Not only did he weld dispart sights on all guns and carronades but also issued wooden quadrant sights (gunners levels) for setting degrees of elevation. To mass fires he had a compass carved at every gunport, with the grooves filled with white putty; using the marks on the compass permitted all gunners to individually set deflections so as to aim at the same common point for given rehearsed ranges, even if the target were obscured from the gun captains' view. Peace nurtures professional complacency. Were it not for the fact that Britian had effectively gained naval supremacy by 1813, and the advent of a long peace thereafter, perhaps his innovations may have made a greater impact. As it was, most captains of most navies were of Nelson's view: “As to the plan for pointing a gun, truer than we do at present, if the person comes, I shall, of course, look at it, or be happy, if necessary, to use it; but I hope we shall be able, as usual, to get so close to our enemies that our shot cannot miss the object.” In fairness it seems that even under ideal conditions navel gunnery was less that accurate against other ships at any sort of range. The guns themselves had a surprisingly long reach - gunnery tables circa 1810 (which were compiled from actual testing on land) show that the 'short ranged' carronade was quite capable of throwing shot as far as all but the largest cannon. The problems for cannon (beyond the fact that the firing platform was in constant motion) seems to have rested in the design of the gun carriage which limited the amount of elevation you could get from the guns. In the case of carronades the problem was actually the barrel design, as unlike cannon the breach was wider than the muzzle (the barrel was the same diameter, but the breach was thicker). This caused problems since gunners were trained to aim by looking down the barrel, which didn't work that well for carronades. Nelson and Collingwood were 'gunnery' officers in as far that they understood that fast and accurate gunnery was what won battles. They made a point of expecting and training their gun crews to manage an (presumably initial) rate of fire of three shots per five minutes - which is impressive considering that the ships they were talking about where first rates with 32 pound cannon. Field guns were a heck of a lot lighter than this, but even here it seems that the Army was very impressed (or as impressed as they would admit to) at the rate of fire naval gunners could manage on land, and even the accuracy they could often show at least against fortifications. The technology and limitations of the guns wasn't something Nelson and Collingwood could really overcome, if only because they could not have managed to get sights for all the ships in their fleets. So they had to fall back on speed and compensate for inaccuracy by getting in close. Of course Nelson and Collingwood had another reason for pushing the idea of getting up close; They were commanding fleets. Even during Nelsons lifetime there was a habit of some captains to avoid close quarter battles, and even the 'Glorious first of June' saw several ships take part in the fleet action by staying as far away as possible and throwing more insults than actual shot. Not only was this far less effective than shot delivered up close, but the chances were that at such range and with the heavy smoke you were just as likely to end up shooting at your own ships than the enemy. The insistence of Nelson and Collingwood about getting in close was really about getting captains to stay with the main fleet, or at least give them no excuse for not doing so. Close range fire was also far more effective, especially from guns where some time was taken to load the guns correctly. This can be seen most clearly from the Battle of Trafalgar and specifically from HMS Victory herself. Victory was underfire for the better part of an hour as she closed with the French and Spanish ships, and apart from a few shots from her chase guns didn't reply until she was right under the stern of the French Flagship. Victories first broadside inflicted more casualties on the French ship than Victory herself would take in the entire battle - even though Victory was at one point being fired into by three different French ships. |

|

|

|

Post by memeengine on Dec 7, 2014 14:55:34 GMT

In the case of carronades the problem was actually the barrel design, as unlike cannon the breach was wider than the muzzle (the barrel was the same diameter, but the breach was thicker). This caused problems since gunners were trained to aim by looking down the barrel, which didn't work that well for carronades. That's probably why most of the carronades in British service, even from the earliest designs, had sights fitted. The rear sight was fitted to a mounting on the breech and the dispart sight was fitted either to a mounting at the muzzle or on the reinforce ring just ahead of the mounting loop. (ref: Arming and Fitting of English Ships-of-War, 1600-1815; B.Lavery, Conway Press, 1987) The problem with hitting a target at range was not so much pointing the gun in the right direction, it was accurately judging the range so that the shot didn't under- or over-shoot. Given the tools available to the gun captains at the time, that was a much trickier challenge. There's a tale of a skirmish at Brest Roads in 1805 where a French first rate (rather unsportingly) fired a full broadside at a British frigate and had the whole lot drop short into the sea. Likewise at Trafalgar, much of the allied fleet's long-range shooting as the British approached either fell short or flew over the mastheads, which meant that the British ships arrived at the line in much better condition than they perhaps should have. This can be seen most clearly from the Battle of Trafalgar and specifically from HMS Victory herself. Victory was underfire for the better part of an hour as she closed with the French and Spanish ships, and apart from a few shots from her chase guns didn't reply until she was right under the stern of the French Flagship. Victory's first broadside inflicted more casualties on the French ship than Victory herself would take in the entire battle... I think that this particular anecdote needs to be taken with a pinch of salt. While it appears in many (otherwise well researched) descriptions of the battle, the claimed number of casualties from the 'first broadside' seem to be hyperbolic. For example, Peter Goodwin's "The ships of Trafalgar" states that the broadside killed or wounded 325 men (but in another section puts the same figure at around 200) and David Lyon's "The Age of Nelson", puts the figure at 400 killed or wounded. Both of these authors are well respected but their fact checking it this respect seems dubious (not that they are alone in this case). My first question is "who counted?". Where did this figure come from? The British were in no position to determine the number of casualties on the other ship so the figure cannot have come from them. So presumably it would have to be a French source. However, as the ship was in the middle of an engagement, who ran around to do the count and when? The ship's surgeon and staff would only have seen the wounded as the dead were left heaped on deck, so they couldn't have given a total. The offiers on the upper decks would only have seen the casualties around them and would have been too busy organising the remaining men to fight and repair damage. Not to mention the difficulty of getting an accurate count from a pile of bodies and body parts. Given that the Bucentaure had a crew of 650-690 (excluding soldiers), a loss of 3-400 men in a single volley (around 50% of the crew) should have put the ship straight out of action, especially when most of the casualties would have been on the gun decks. However, we know that she fought on for at least another hour. From the French casualty reports at the end of the battle, the Bucentaure had somwehere between 200-290 killed or wounded (including those lost in the storm and sinking of the ship). If we try and reconcile these figures, even with the lowest of the estimates, we would have to assume that all of the Bucentaure's casualties were from that first volley. That would mean that the subsequent raking broadsides from the 98-gun Neptune and the 74-gun Leviathan and Conqueror, which followed the Victory across the Bucentaure's stern, caused no casualties at all. As the broadside from the Neptune is also quoted as killing half the remaining men on the lower gun deck, this can't be the case. The truth is we're in no position (and probably never will be) to know exactly how devastating that initial raking broadside from the Victory was. And then there's also the minor question of whether that was the Victory's first broadside. I've read accounts which quote the Victory's gunner stating that the ship fired its first broadside into the Santissma Trinidad (which was immediately ahead of the Bucentaure) as the Victory turned to go astern of the French flagship. |

|

|

|

Post by Cybermortis on Dec 7, 2014 17:05:12 GMT

Educated guess would be that the figures came from the French Surgeon. Of course 'casualties' would cover everything from men killed outright to those who were knocked out or stunned and taken below but who were able to go back to the guns later in the battle. It is also possible that the initial attack simply resulted in knocking one of the gun decks* out of action temporarily, and the British though this was down to killing most of the gun crews.

(*The Bucentaure was an 80 gun ship, meaning she was a second rate ship of the line and hence actually outgunned by Victory. The paintings of the ship seem to show she had two full gundecks, plus there would have been additional guns on the weatherdeck.)

It might also be a case that a lot of the initial casualties were from the soldiers rather than the sailors, which might not actually affect the ships ability to fight. Or or course the soldiers may have been able to replace some of the guncrews who had been injured or killed.

The low quality of French gunnery, at least in 1805, was a side effect of the revolution. Revolutionary France got rid of practically all 'noble' personal in the military and navy. While this mainly removed experienced and skilled Captains and Admirals, I'd guess that this would also have included a lot of the gunners. (And Napoleon most likely had most of the remaining experienced gunners moved to the Army) Coupled with being stuck in port, and hence unable to do any sort of live-firing practice, this would have resulted in a very pitiful standard of gunnery in the French fleet (not helped by poor quality powder).

The British in comparison had well trained and experienced gunners and gun crews - even those who had never fought at the Nile or in another fleet action would most likely have had a chance to fire at something when they were serving on Frigates.

Aside; Line ships did occasionally open fire on Frigates, sometimes by accident (it could be easy to mistake a frigate for a larger ship in the thick of fighting, especially if aiming through a gunport and trying to look though thick smoke) other times because the Frigate was seen as a threat. Typically because the frigate had fired at the bigger ship or was thought to have done so.

Usually Frigates were left alone, probably less to do with 'honor' and more to do with practicality; Why waste shot on a ship that wasn't a major threat when you could fire at something bigger and nastier? Besides, the Frigate you were firing into was most likely sailing around picking up sailors from the water.

|

|